|

||

|

Charles Schulz

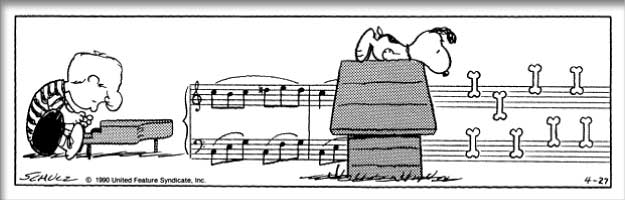

Peanuts • 04/27/1990

About the StripThe Charles M. Schulz Museum has access to approximately 7,000 of the 17,897 comic strips drawn by Schulz during his nearly 50-year career. The Museum does not own the Schulz originals of many of the comic strips selected for this exhibition; the strips displayed are reproductions of published Peanuts comics. The reproductions of Schulz's original comic art owned by the Museum are noted throughout the on-line exhibition. Schulz's original art contains many fascinating details that offer a glimpse into his creative process. Pencil lines can often be seen under the ink. However, Schulz did not "ink in" as did many cartoonists. That is, he didn't first draw the strip in pencil and then go over the pencil lines with pen and ink. Schulz used light pencil lines to provide guidelines for spacing. He preferred the spontaneity of drawing the facial expressions in ink without much pencil underneath. When Schulz drew a smile or a frown, he said he was actually feeling that emotion. In addition, sometimes it is possible to see eraser marks, correction fluid, or places where text or images have been glued over something else. In this panel (right) from the Hammerklavier strip from January 25, 1953, Schulz made Schroeder jump slightly higher, changed the position of his ear, redrew his mouth, and moved the door and doorknob from their original positions. All these changes make the panel more animated. Schulz also sometimes used Zipatone to add shading and dimension to the strip. Zipatone, a transparent adhesive film covered with patterns of dots, was used to produce gray tones. The adhesive film was placed over the portion of the strip to be shaded and the remainder of the film was cut off with an artist's knife. Zipatone is no longer used by cartoonists. Now they employ computer software to achieve the same effect. In this daily strip above (April 27, 1990), Zipatone was applied to Snoopy's doghouse and Schroeder's piano. Some people are surprised to see original Peanuts Sunday strips - first because the originals are not colored and second because they may never have seen the top third of the strip in the version published in the newspaper. That portion of a Sunday strip is called the "throw-away panel." Depending upon the amount of space each newspaper has for its Sunday comics, they might print only the bottom two-thirds of a strip. Thus, the top third relates to the rest of the strip but cannot be integral to the story. From the first Sunday strip in 1952 until 1999, the process of coloring the Sunday Peanuts remained relatively the same. After Schulz completed an original Sunday strip, a copy was made to which he assigned a color for each area (the colors were based on a printer's color chart). The copy was then hand-colored, usually by Schulz's secretary. When Schulz was satisfied with the colors, the hand-colored copy and the original strip were mailed to United Feature Syndicate (UFS) in New York for distribution to newspapers nationwide. In 1999 this process became digital. The coloring was done on computers, and the digital files were then sent to UFS. Although no new Sunday strips have been created since February 2000, artists at Schulz's studio digitally color the older Sunday strips that are reprinted in newspapers today (the original hand-colored versions are not available). |

|

|